As it stands, the argument for Bitcoin as money has several components which could be called into question.

This is an opinion editorial by Taimur Ahmad, a graduate student at Stanford University, focusing on energy, environmental policy and international politics.

Author’s note: This is the first part of a three-part publication.

Part 1 introduces the Bitcoin standard and assesses Bitcoin as an inflation hedge, going deeper into the concept of inflation.

Part 2 focuses on the current fiat system, how money is created, what the money supply is and begins to comment on bitcoin as money.

Part 3 delves into the history of money, its relationship to state and society, inflation in the Global South, the progressive case for/against Bitcoin as money and alternative use-cases.

Bitcoin As Money: Progressivism, Neoclassical Economics, And Alternatives Part I

Prologue

I once heard a story that set me on my journey to try and understand money. It goes something like:

Imagine a tourist comes to a small, rural town and stays at the local inn. As with any respectable place, they are required to pay 100 diamonds (that’s what the town uses as money) as a damage deposit. The next day, the inn owner realizes that the tourist has hastily left town, leaving behind the 100 diamonds. Given that it is unlikely the tourist will venture back, the owner is delighted at this turn of events: a 100 diamond bonus! The owner heads to the local baker and pays off their debt with this extra money; the baker then goes off and pays off their debt with the local mechanic; the mechanic then pays off the tailor; and the tailor then pays off their debt at the local inn!

This isn’t the happy ending though. The next week, the same tourist comes back to pick up some luggage that had been left behind. The inn owner, now feeling bad for still having the deposit and liberated from paying off their debt to the baker, decides to remind the tourist of the 100 diamonds and hand them back. The tourist nonchalantly accepts them and remarks “oh these were just glass anyways,” before crushing them under his feet.

A deceptively simple story, but always hard to wrap my head around it. There are so many questions that come up: if everyone in the town was in debt to each other, why couldn’t they just cancel it out (coordination problem)? Why were the townsfolk paying for services to each other in debt — IOUs — but the tourist was required to pay money (trust problem)? Why did no one check whether the diamonds were real, and could they have even if they wanted (standardization/quality problem)? Does it matter that the diamonds weren’t real (what really is money then)?

. Peter remarked how this made sense but felt so counter to the prevailing narrative.

Even if we take the monetarist theory as correct, let’s get into some specifics. The key equation is MV = PQ.

M: money supply.

V: velocity of money.

P: prices.

Q: quantity of goods and services.

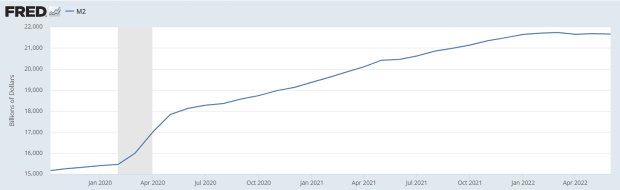

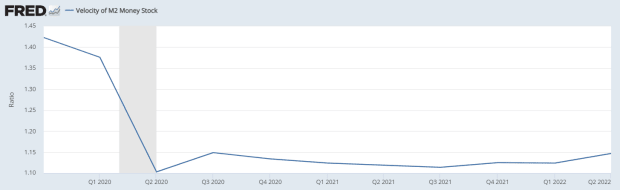

What these M2 based charts and analyses miss is how the velocity of money changes. Take 2020 for example. The M2 money supply surged higher because of the fiscal and monetary response of the government, leading many to predict hyperinflation around the corner. But while M2 increased in 2020 by ~25%, the velocity of money decreased by ~18%. So even taking the monetarist theory at face value, the dynamics are more complicated than simply drawing a causal link between money supply increase and inflation.

As for those who will bring up the Webster dictionary definition of inflation from the early 20th century as an increase in money supply, I’d say that change in money supply under the gold standard meant something completely different to what it is today (addressed next). Also, Friedman’s claim, which is a core part of the Bitcoiner argument, is essentially a truism. Yes, by definition higher prices, when not due to physical constraints, is when more money is chasing the same goods. But that does not in and of itself translate to the fact that increase in the money supply necessitates an increase in prices because that additional liquidity can unlock spare capacity, lead to productivity gains, expand the use of deflationary technologies, etc. This is a central argument for (trigger warning here) MMT, which argues that targeted use of fiscal spending can expand capacity, particularly through targeting the “reserve army of the unemployed,” as Marx called it, and employing them rather than treating them as sacrificial lambs at the neoclassical altar.

To bring this point to a close then, it’s hard to understand how inflation is, for all intents and purposes, anything different to an increase in CPI. And if the monetary expansion leads to inflation mantra does not hold, then what is the merit behind Bitcoin being a “hedge” against that expansion? What exactly is the hedge against?

I will admit there are a plethora of issues with how CPI is measured, but it is undeniable that changes in prices happen because of a myriad of reasons across the demand-side and supply-side spectrum. This fact has also been noted by Powell, Yellen, Greenspan, and other central bankers (eventually), while various heterodox economists have been arguing this for decades. Inflation is a remarkably complicated concept that cannot be simply reduced to monetary expansion. Therefore, this calls into question whether Bitcoin is a hedge against inflation if it is not protecting value when CPI is surging, and that this concept of hedging against monetary expansion is just chicanery.

In Part 2, I explain the current fiat system, how money gets created (it’s not all the government’s doing), and what Bitcoin as money could lack.

This is a guest post by Taimur Ahmad. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC, Inc. or Bitcoin Magazine.